From Tinnitus to Tomorrowland: How Loop Rebuilt the Culture Around Hearing Protection

You’re front row for your favorite artist. The lights flash and the bass reverberates through your body all night long. After the show is over, the adrenaline wears off, but something else lingers—a high-pitched ringing that certainly wasn’t part of the set. You brush it off and the ringing fades the next day. But what if it didn’t?

That’s the question Maarten Bodewes—co-founder of Loop Earplugs—found himself asking after a night out during college nearly seventeen years ago. He stood too close to a speaker and ended up with tinnitus (the perception of ringing, buzzing, or other phantom sounds in the ears) for weeks. That moment became the catalyst for Loop, a hearing protection brand that’s now sold over 11 million earplugs across 150 countries.

All those years ago, Loop was just an idea born of pain. It was a wake-up call for Bodewes, not just about hearing damage, but about the lack of hearing protection options. He began testing all the earplugs available at the time, but they were "ugly foamies or awkward transparent ones that stuck out of your ears," Bodewes told EDM.com. They were uncomfortable, distorted the music, and worst of all, made wearers feel like they didn’t belong in the room. "People dress up to go out," he said. "No one wants to ruin their look with something clunky sticking out of their head."

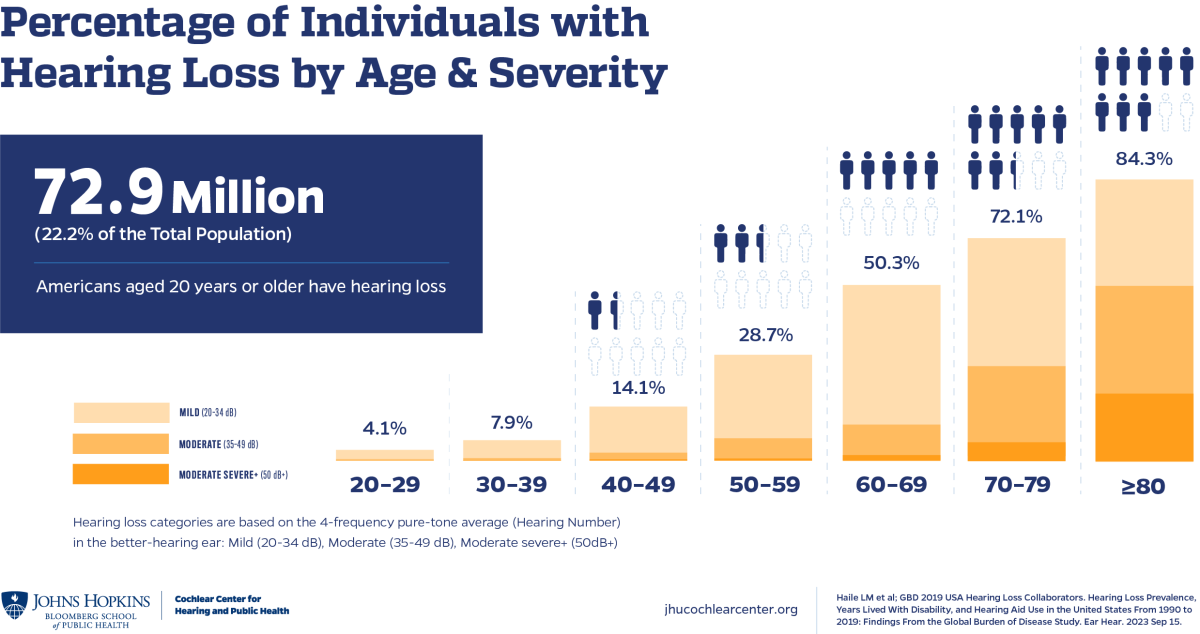

The statistics are sobering. The World Health Organization estimates that around 1.1 billion young people are at risk of hearing loss from unsafe listening practices at concerts and festivals. Plus, a 2023 EDM.com poll found that nearly half of music festival attendees don’t wear ear protection.

Some feel earplugs will ruin the music. For others, the post-show ringing in the ears is part of the experience. A temporary buzz, maybe even a badge of honor. But audiologists and researchers say that sensation—referred to in the scientific community as a "temporary threshold shift"—is actually your ears begging for help. This sensation commonly affects artists as well. Martin Garrix and Alesso have both spoken publicly about the impact of tinnitus on their careers.

Part of the problem is that people don’t realize how quickly the damage can set in. Exposure to high volumes, even briefly, can have long-term consequences. To make it worse, the ears don’t have pain receptors, so unlike a cut or burn, hearing damage doesn’t trigger immediate physical pain. By the time the ringing or muffled hearing kicks in, the harm may already be done.

According to the National Institutes of Health, hearing loss can begin at just 85 decibels (dB). The average electronic music concert clocks in at 100–112 dB, with front-row levels often spiking to 120 dB or higher. That’s more than enough to cause permanent damage in under 15 minutes. Exposure to those sound levels overstimulates delicate hair cells in the inner ear, which are the microscopic structures responsible for translating vibrations into sound signals. Once damaged, they cannot grow back. This results in long-term hearing loss, tinnitus, and increased sensitivity to noise over time.

These risks propelled Bodewes to sketch a different vision for earplugs. He believed hearing protection should be less of a compromise and more of an accessory. "I love everything that's loud, whether that's festivals, concerts, fast cars or motorcycles," Bodewes described his passion for sound. He wrote his college thesis on reinventing earplugs, and while holding a day job at Microsoft, spent nights and weekends attempting to create a new type of earplug with longtime friend Dimitri O.

In 2016, they launched Loop’s prototype and pitched it to a Belgian startup accelerator. After getting accepted, Bodewes immediately quit his job and poured all his savings into Loop. Going all in like that was tough but necessary. "I'm not very risk averse. If I drive a motorcycle, I drive all out, if I play poker, I go all in quite often," Bodewes said about ditching stability to pursue his passion. "If you want to solve a problem that you face personally, you're very motivated, it’s not about making money."

The early Loops were 3D printed and spray-painted by hand in Bodewes’ backyard. They were sold mostly to friends and family. Through word-of-mouth and a growing reputation for quality, Loop started gaining traction.

As momentum built, Loop doubled down on the scene that inspired it in the first place—nightlife. "We always went to festivals and Tomorrowland was just 10 kilometers from where we lived," Bodewes shared about his personal connection to dance music. He describes his tastes as "100% electronic music." At home, Bodewes enjoys listening to Lane 8’s seasonal mixtapes and other melodic house artists like Ben Böhmer. He also recounts Pete Tong, Swedish Mafia, and deadmau5 as some of his favorite live performances. He even named their website loopnightlife.com and signed emails off as "Nightlife Evangelist."

Bodewes' enthusiasm and understanding of the electronic music community inspired him to position Loop differently than other earplugs. The product was marketed as liberation instead of protection, desire instead of guilt. "Other brands said, ‘It’s too loud, protect yourself,’" he pointed out. "But our message was, ‘go front row.’"

Loop's mindset resonated with ravers and club-goers who had grown tired of choosing between their hearing and the music. "If you wear earplugs, you can go out longer and be closer to the stage," Bodewes emphasized about Loop’s mantra. "It's more comfortable and you go home without a beep in your ears."

While most earplugs sacrifice sound quality for protection, Loop set out to do both without compromise. Traditional foam plugs often distort the listening experience, muffling music and cutting off certain frequencies entirely. The result feels like you’re hearing the show through a wall.

Loop’s approach was different. They engineered and patented a circular acoustic channel—roughly the length and curve of the human ear canal—to reduce volume without degrading clarity. Paired with a precision mesh filter, this setup helps preserve the full frequency range of sound by filtering sound waves rather than blocking them, so you still feel the bass and hear the highs, just at a safer, more sustainable level.

Research backs up what Loop offers. A randomized controlled trial published in JAMA Otolaryngology found that concertgoers wearing earplugs experienced significantly less hearing loss and tinnitus than those who didn’t.

Ear protection is becoming part of rave culture’s uniform. And with brands like Loop leading the way, the message is clear: you don’t have to choose between hearing your favorite drop now and being able to hear it again five years later.

But great sound isn’t enough. If earplugs aren’t comfortable, no one would keep them in long enough to prevent hearing damage. Most earplugs are a one-size-fits-none situation. They either slip out mid-set or dig into your ear canal after an hour.

Loop prototyped dozens of designs to fix that. They tested different insertion angles, canal lengths, and tip materials using electronic dummy heads and 3D-printed mockups. The final result was a system of soft-touch, food-grade silicone ear tips that come in multiple sizes, paired with an ergonomic loop-shaped shell that evenly distributes pressure. This design doesn’t just make the earplugs more comfortable, it keeps them stable during movement, crucial for when you're dancing at a music festival.

The improved fit also helps reduce the occlusion effect—the frustrating phenomenon where one's voice or footsteps sound oddly amplified when you block your ears. By minimizing this, Loop earplugs feel more natural and breathable. You forget you're wearing them.

Solving comfort and sound was critical, but making people want to wear earplugs meant getting the design right as well. Most earplugs on the market looked disposable. They were foam sticks or translucent cones you hoped no one noticed. You wore them in spite of how they looked.

Loop wanted to flip that. The goal wasn’t just to make earplugs less ugly; Bodewes wanted them to feel like jewelry. "Sometimes I compare earplugs to sunglasses," he said. "They started as functional tools for pilots, now they’re a fashion staple." That same logic drove Loop’s approach. Their signature circular design is fashion-forward. It doesn't scream hearing protection. Instead, it’s sleek and expressive.

Colorways played a big role in Loop’s form factor as well. Bodewes saw earplugs as an extension of identity. From subtle neutrals to reflective metallics, Loop offers options that work with your outfit, not against it. Limited-edition collaborations, seasonal drops, and soft-touch finishes helped position the brand not just as a tool but as a lifestyle accessory and form of self-expression.

In 2019, the New York Times named Loop the best earplug for concerts. "That gave us a really good boost," Bodewes noted. "We expanded into retail, partnering with chains like CVS in the USA and Saturn in Europe, and became profitable by the end of 2019." But growth came with new challenges. "In the beginning, we thought we could scale 3D printing all the way, but if you do really high volumes, that's difficult." Bodewes shared. "When we moved to injection molding, the first run came back with warped plastic and we had to fly to China and fix the products by hand."

Loop overcame those early hurdles and found its footing, scaling quickly and reaching a broader audience faster than they ever expected. "Fifty to sixty percent of our customers never bought earplugs before," Bodewes revealed. "We're creating that category as we go."

One milestone still loomed large, bringing the brand to Tomorrowland. "It was in our minds from the very start," Bodewes affirmed. "We went to Tomorrowland, even when it was small, and had a personal motivation to see our product at that festival."

It took almost five years of growth, iteration, and relentless pitching to make it happen. "We had to be grown up enough to work with them," Bodewes explained, referring to the level of product polish, brand maturity, and marketing muscle required to partner with arguably the most prolific electronic music festival in the world.

Loop’s first official partnership with Tomorrowland launched in 2022. But it wasn’t just a sponsorship. Loop created custom earplugs specifically for the festival, even adjusting the carry case, packaging, and accessories to match the Tomorrowland aesthetic. The limited-edition earplugs featured a gold-accented ring and the words "Live, Love, Unite"—a nod to the festival’s iconic slogan. The case was designed to resemble a compass, symbolizing sound as a guide.

Now, with the 2025 edition of Tomorrowland around the corner, Loop is entering its fourth year partnering with the festival.

This year, Loop has hit another milestone. They became Coachella’s first official earplug partner. To mark the occasion, the Loop released custom earplugs featuring a desert-sunset gradient, sold on-site at the festival grounds and online.

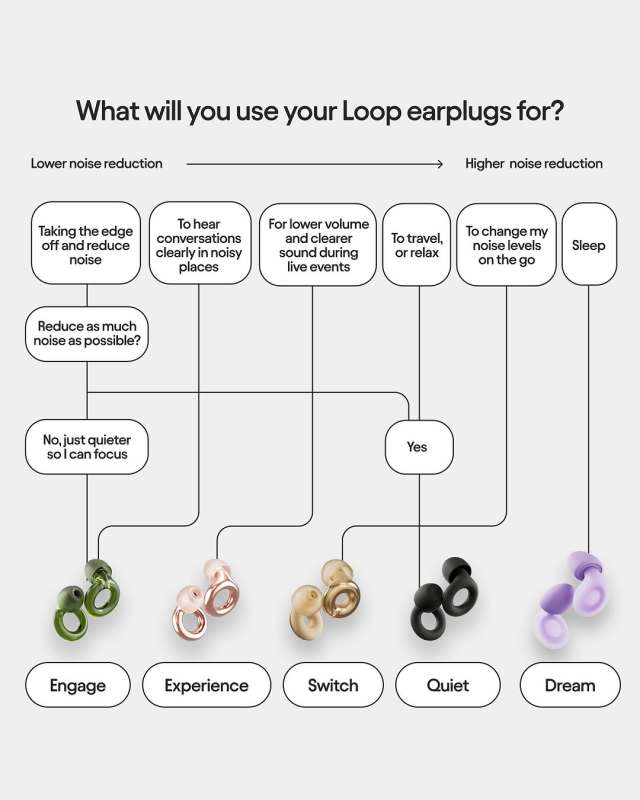

Loop has also ventured outside the music world, partnering with McLaren Racing earlier this year. These earplugs featured the team’s signature papaya orange and carbon black while spotlighting Loop’s most advanced model yet, the Switch 2. Unlike traditional earplugs, which offer a single level of noise reduction, the Switch 2 lets users toggle between three distinct modes—"Quiet," "Experience," and "Engage"—with a discreet rotating dial built into the ring. It’s a design that mirrors the McLaren ethos: precision, control, and adaptability.

What started as a niche product has now become part of the culture. "In the beginning, it was a game for us to find the first person wearing Loops out in the open," Bodewes beamed. "Now, you go to the front row of a festival and everyone’s wearing them. It’s really cool to see that shift."

That kind of global visibility might seem inevitable now, but a few years ago, Loop nearly lost everything. When the pandemic hit in early 2020, nightlife shut down overnight, and so did Loop’s core customer base. "Our revenue dropped almost 90 percent in just two weeks," Bodewes recalled. "No more festivals, no more going out, and retail stopped ordering entirely."

It was a make-or-break moment. Instead of waiting it out, Loop adapted. They pivoted to a fully direct-to-consumer model. People stuck at home—parents, students, remote workers—started buying Loop earplugs not for parties, but for peace and quiet. Others turned to Loop for help with overstimulation, sensory processing, or better sleep.

That wave of unexpected demand led to the release of Loop Quiet, earplugs built for calm. Designed with soft-touch materials and optimized for long wear, it helped reposition the brand beyond nightlife. The messaging evolved as well. They shifted their tagline from "Protect your ears in style" to a more inclusive ethos, "Your life, your volume."

This wasn’t just a clever rebrand. It was a survival strategy that unlocked new audiences and use cases, ones that now make up a significant share of Loop’s growth today. "We now ask ourselves how we can empower people to live fully whether they want to go loud at a festival, focus during the day in a busy office, or sleep on a plane," Bodewes stated.

Orders started pouring in from people craving focus, calm, or simply less noise—parents in loud homes, overwhelmed students, remote workers in shared spaces, and light sleepers in need of rest. A particularly meaningful wave of users came from the neurodivergent community—people with autism, ADHD, sensory sensitivity, or anxiety. For those who experience auditory overload, even routine environments can feel like an assault. Loop offered a way to soften the edges of the world and turn the volume down without shutting everything out.

"When we started Loop, we didn't think of being able to help like this," Bodewes marveled. "Now, when we hear stories about how it helps people walk around, be at family events, be in the classroom, and stay more calm, it touches our team quite a lot."

What began as a rave accessory has evolved into a tool for everyday resilience. Loop isn’t just helping people hear better—it’s helping them feel safer, calmer, and more at ease in their own lives.

Looking ahead, the company is expanding into new categories and audiences. "We’re working on four or five new products, some in the hearing space, some beyond," Bodewes revealed. "We’re going to use electronics and advanced tech and there's going to be a lot of cool new collaborations coming in sports and fashion too." Loop is no longer a scrappy startup. It has 300 employees and offices in Antwerp, Belgium, as well as Amsterdam, New York City, and Shanghai.

"We’re still building for that 10% though," Bodewes emphasized, referencing the early days when 90% of people thought no one would buy fashion-forward earplugs. "Sometimes our ideas may split opinion but we have to trust our gut."

For Bodewes, the goal is still the same as it was almost two decades ago: give people control over how they experience the world, whether that means turning it down or tuning back in.

.jpg)

/origin-imgresizer.tntsports.io/2026/01/11/image-e0142c20-61a4-495b-a1c4-a9e1cf7eeecb-85-2560-1440.jpeg)

:format(webp)/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/66321622/1206682849.jpg.0.jpg)

:format(webp)/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/67131045/1261725039.jpg.0.jpg)

/origin-imgresizer.eurosport.com/2024/02/04/3880159-78836108-2560-1440.jpg)